The first volume of My Favorite Thing is Monsters makes no judgments about art. As the first half of a planned two-volume series, this debut book incorporates art from everywhere, from horror magazines to classic paintings found in the Art Institute of Chicago. But for Karen, the young protagonist of Ferris’ book, there’s no difference in the meaning or in the value of the art. Pulp art and fine art are the same things and each has an equal influence on how she sees the world after a neighbor is killed in an upstairs apartment. As the young girl tries to unravel the mystery of who killed her neighbor and friend Anka, the world around her is changing in both monumental and minuscule ways, and in many of these seismic shifts are not even related to the murder. Against the civil unrest in America, Karen and her brother also have to deal with their mother, who is far sicker than she lets on to her daughter. Ferris’ book is broad in its approach, looking at the lives of both Karen and Anka but incredibly focused on this girl who has to learn at an early age about the spiritual murkiness of the world.

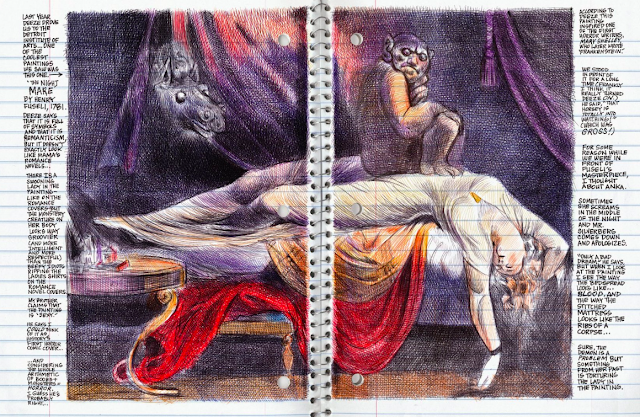

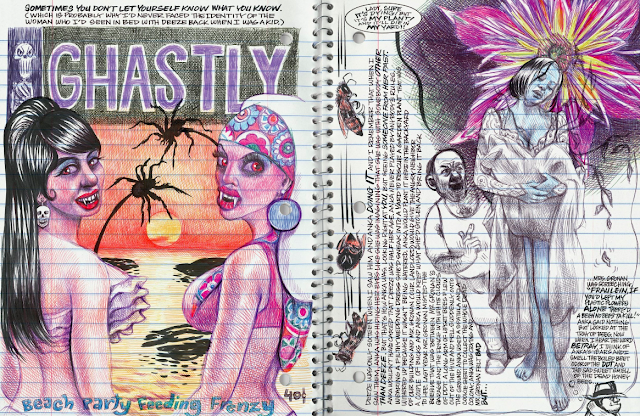

For most people, a ballpoint pen is a conveniently clumsy device for taking notes or scribbling doodles but for Ferris, it’s as expressively lush as any brush ever set to canvas. Drawn in a schoolkids’ spiral-bound notebook, every page of this book reminds you that Ferris is telling this story through the eyes of a young, adolescent girl. This is Karen’s journal as much as it is Ferris’s book and we see the world as Karen does, informed by monster magazines and centuries-old paintings. Karen’s own self-image of herself is as one of those monsters but for her being a monster is not a curse but an aspiration. Picturing herself as a young werewolf private eye, complete with fangs, trench coat, and fedora, Karen is on the case, chronicling the men, women, boys, and girls she runs across as she tries to make sense of her neighbor’s murder.

Every page of Ferris’s work is in itself a piece of art, longing to be observed, absorbed and lived. That’s what’s arts is in Karen’s Chicago; it’s a part of life and it doesn’t matter if it’s in a pulp magazine, in a museum, or even if it’s a tattoo on her brother’s body. In telling a story about a murder, Ferris is also creating a story about art and the ways that it shapes us and our own worldviews. As a young girl and a bit of an outcast, she identifies more with the werewolves, Frankenstein monsters, and werewolves from her beloved magazines more than she does with most of the girls and boys her own age. And in a time where both her neighbor and Martin Luther King Jr. can be killed, it must make a lot of sense to see everyone else in Chicago as one of those mobs out to destroy the beauty and souls of those monsters.

Trying to solve a mystery as only a 10-year-old girl can, Karen is forced to grow up and learn truths about her neighbor Anka, a European Jew who survived World War II, and about her brother Deeze, a local lothario who is haunted by his own demons. Karen is still young so her own demons are self-imagined and self-projected; she’s the innocent in a world which seemingly abhors innocence. While Anka and Deeze’s demons are more formed, they are still reflected in their faces just as Karen’s are. But where Karen thinks she wants to be her own type of demon, these people who she thinks she knows hide their demons from Karen. They have lives and experiences that Karen doesn’t know anything about. As she tries to play detective, it’s difficult to know just how much of the truth of the world is changing her.

Set in 1968, Ferris’s story is a long way away from any “summer of love” or any “peace, love and happiness” sentiments. It’s important to realize the time of this book as the world then was falling apart socially and politically even as our modern day seems to be on the brink of some kind of collapse as well. It’s not that Ferris has created a political book but she acknowledges that politics are a part of our lives that influence us. Karen’s politics are what she knows from her mother and her brother so you have to wonder how do events like the assassinations of President Kennedy (a memory for her) and Martin Luther King Jr. (an event that happens during this book) affect how she sees the world.

Chronicling her investigation in a ruled-line notebook, Karen’s visions of the world alternate between incredibly beautiful and monstrously ugly. Anka is usually drawn with a blue pen, shading her in a chilling beauty. Others get this same blue line, giving them the icy appearance without the beauty. Karen’s image of the world acknowledges and accepts the coexistence of beauty and ugliness. Ferris’s depiction of late 1960s Chicago is a tapestry of types and a more honest portrayal of the makeup of a city months away from rioting at the Democratic National Convention. Again, it’s not the politics of the story that influence Karen but it’s how those politics flavor the atmosphere of Ferris’s story.

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters is a child’s romanticized view of an ugly world. Emil Ferris gives us a violent, horrific Chicago that is full of real monsters and people who are unfairly labeled as “monsters.” And among all of that, we have Karen, our innocent child who wants to be a monster even though she is anything but one. Her desires come from the magazines and movies she enjoys but it’s also a desire to be strong enough to face the real terrors that live in her neighborhood and maybe even in her building. Even as she hides behind her fantasies, Karen has to learn to see the world beyond those fantasies. Emil Ferris’ book perfectly captures that moment in our lives where we’re between seeing the world through a child’s eyes and understanding it from an adults point of view.