It is 2020, and our collective knowledge of depression has advanced rapidly. While we are by no means free of stigma surrounding mental health, there is certainly more freedom of expression surrounding it. Though it's almost certain that the internet and social media contribute heavily to many of our mental health concerns, particularly depression and anxiety, it's also true that they have become supportive outlets for people to process their feelings, and they have opened up a community of sharing and support.

I honestly had no idea what The Dark Matter of Mona Starr was about when I put it on hold at my library. I wasn't familiar with the author at all, and I didn't read anything much about the book when I checked it out. I thought perhaps it would be a fun science-fiction story. Instead, I was immersed into a staggeringly beautiful account of depression that tells a more complete story about the affliction than I'm used to seeing, and one that finds a way to be earnestly uplifting and prescriptive in all the right ways.

The best result of opening a dialogue about mental health is that we have started to step out of the terrible pop-culture stereotypical depictions of depression and anxiety, ones that either over romanticizes or demonizes the conditions, ostensibly looking for some palatable way to portray illnesses, but actually only increasing the "otherness" of these conditions. You're familiar with the type - the depressed misanthrope, the anxious neurotic, or the inexplicable conflation of schizophrenia symptoms with bipolar disorder. And certainly, at least the first two do exist with some degree of prevalence within the diagnoses, but they are nowhere near the typical case that movies and television have sold to us. There's also the casually pejorative dismissal of mental illness, disorders, or conditions - anyone moody is bipolar; anyone who is meticulous has OCD; excitable kids have ADHD; anyone whose socialization is suspect is on the spectrum. And though we have a better collective understanding and measurably more empathy around mental health, almost the entirety of that achievement should be credited to people who put their own symptoms out in the open to break the mystique surrounding these feelings. and to - quite bravely I should add - welcome people into their minds and hearts.

Laura Lee Gulledge creates perhaps the truest sense of how depression picks away at its victims with her beautifully constructed graphic novel, The Dark Matter of Mona Starr. In this singular work, she is able to honestly construct the feelings associated with both depression and social anxiety, coupled with the typical strains of adolescence that would wreak havoc on anyone's emotional psyche. She creates a lovable protagonist in the titular Mona, a young lady who captures the reader's heart and attention from the first few pages. Moreover, Gulledge provides not only an accurate narrative of the manifestations of depression, but also a road map out of those feelings. It's all too en vogue in young adult literature and pop-culture in general to focus on the symptoms of mental health concerns. But Gulledge's work is both informative and tender, and she tackles the whole scope of depression better than I've read elsewhere.

People without depression often have difficulty grasping the nature of the affliction. What exacerbates some of this is the all too infrequently discussed delineation between feelings and actual clinical diagnosis. Everyone feels depressed from time to time, but not everyone has depression, even if your depressed feelings extend longer than the normal, even if the trigger - a death, a personal failure - is the same as a triggering event for people with clinical depression. Everyone feels anxious, perhaps before a test or job interview, or in the early stages of a relationship. It is perfectly normal to feel anxious before a job interview, and it's entirely understandable to feel depressed if you've missed out on that job. What isn't - and I hesitate to use this word - normal is the kind of crippling feeling associated with depression. What gets lost in the Hollywood interpretations of depression is the visibility aspect. There is a tendency, if not a direct need, to exaggerate the visibility of some mental health symptoms in order to make it palpable for audiences. Some prose has done a remarkable job capturing these feelings, but it is obviously limited by its form as well.

Cue graphic fiction, uniquely suited to give the reader a fuller picture of mental health. In film or prose, it can be difficult to describe the visual components of depression without over-narrating. Hence the rise of the veritable cottage industry of Instagram mental health comics. Some of these are wonderful snapshots, and one gets the sense that they provide great coping mechanisms for their creators. And surely, it's nice to flick across a feed to find something that succinctly captures your feelings. However, through Mona Starr, Laura Lee Gulledge gives readers the full story, from triggering events, to spiraling feelings, to emergence and coping.

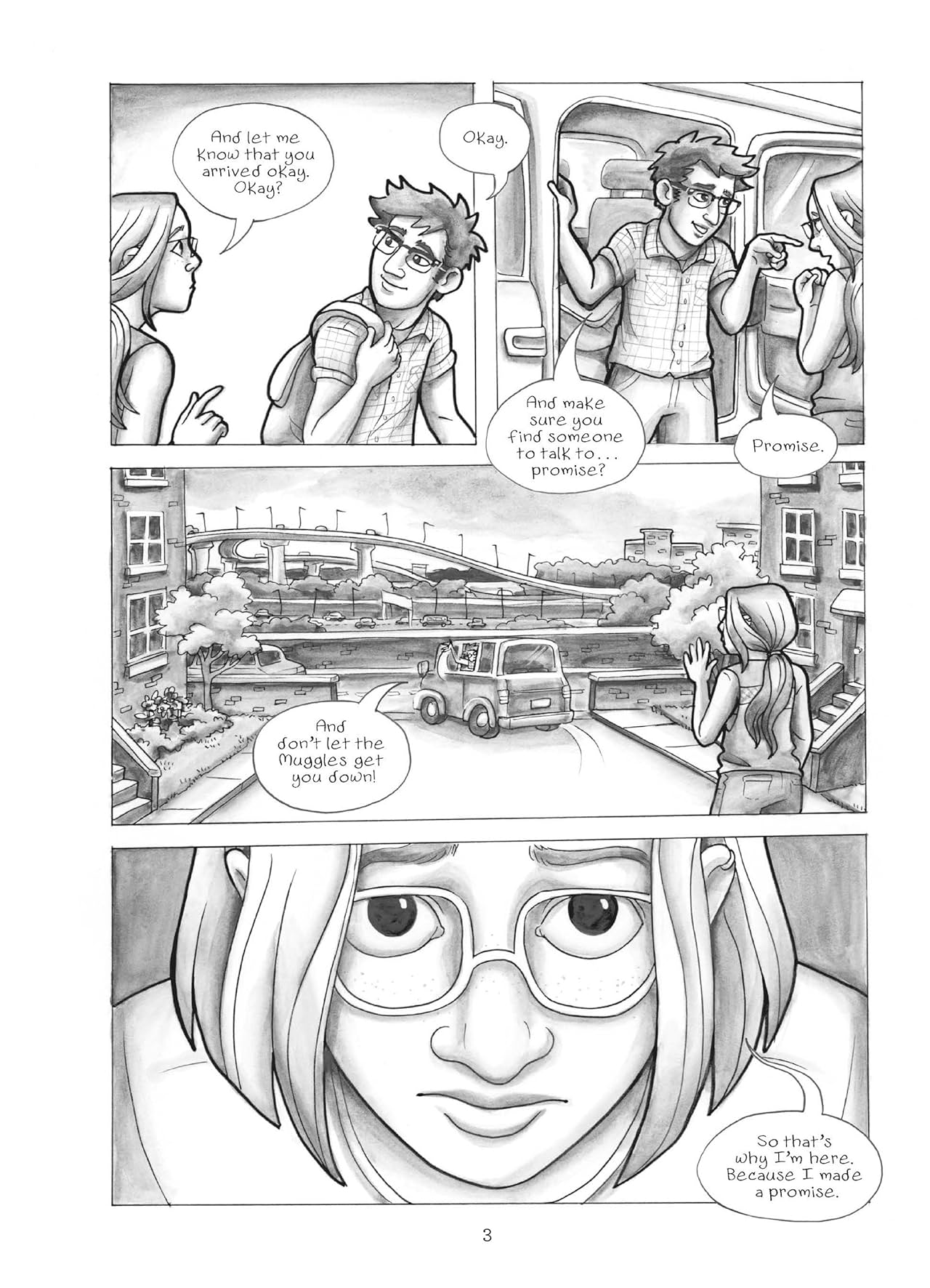

Dark Matter begins with Mona coming to terms with her best friend Nash's move to Hawaii. We get the sense that Mona has been struggling with something, and Nash makes her promise to "talk to someone" before he departs. Mona does, but she can't truly de-center herself. Or perhaps that is the wrong way to put it. Perhaps she is all too adept at de-centering herself. She is caught up in her own apparent insignificance that she has convinced herself that her burdens are not worth assessment. There are people with worse problems, so why should she waste anyone's time on hers. Such a feeling is all too common with depression, but that natural selflessness is also what makes Mona a lovable, compelling character. That she often can't overcome her own burdens to show her selflessness is an obstacle in itself. That she often can't overcome her own burdens to show her selflessness is an obstacle in itself, and, like everything related to depression, obstacles tend to snowball.

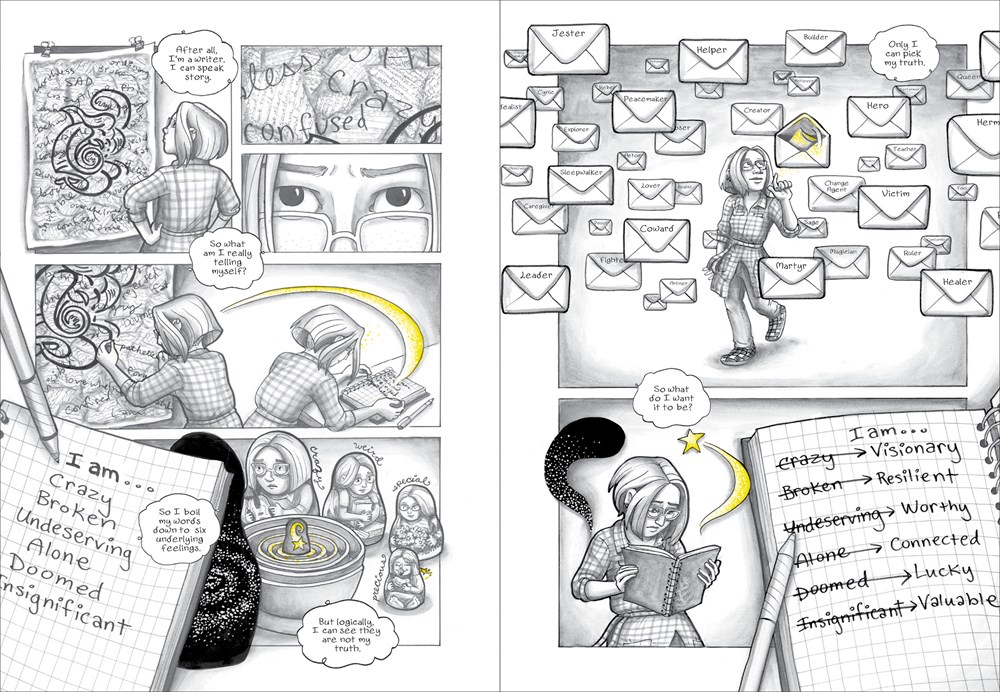

Mona's story is familiar. She naturally relates her feelings of isolation. Nash was one of the only people with whom she could feel a degree of comfort; he was the only one she would open up to, and he was the only person Mona feel could accept her for who she is. His departure coupled with the beginning of a new school year was more than enough to trigger some ugly feelings of sadness and self doubt. It's in this sequence that Gulledge does wonderful work distinguishing depression from anxiety. They certainly co-occur, and both definitely feed the other. Moreover, the end result can often include a withdrawal. But there is a different element between each. Anxiety often manifests in feelings of hypotheticals, of a firm knowledge that the outcome for a particular event will be terrible. Thus, the easiest thing to do is avoid that event, situation, or person. With depression, there is a more pronounced feeling of universal worthlessness, and Mona's actions speak to this delineation. It isn't that she is afraid she will embarrass herself, it's more that she is certain no one wants anything to do with her. She distrusts herself as a result. She does not believe in her art because she thinks no one else will, even though she knows she isn't a bad artist. She knows she wouldn't necessarily be laughed at for what she produces. But she is confident that it simply isn't good enough to be special, and that depresses her further. Mona struggles to make friends because she can't open up about who she is because there is a degree of shame there.

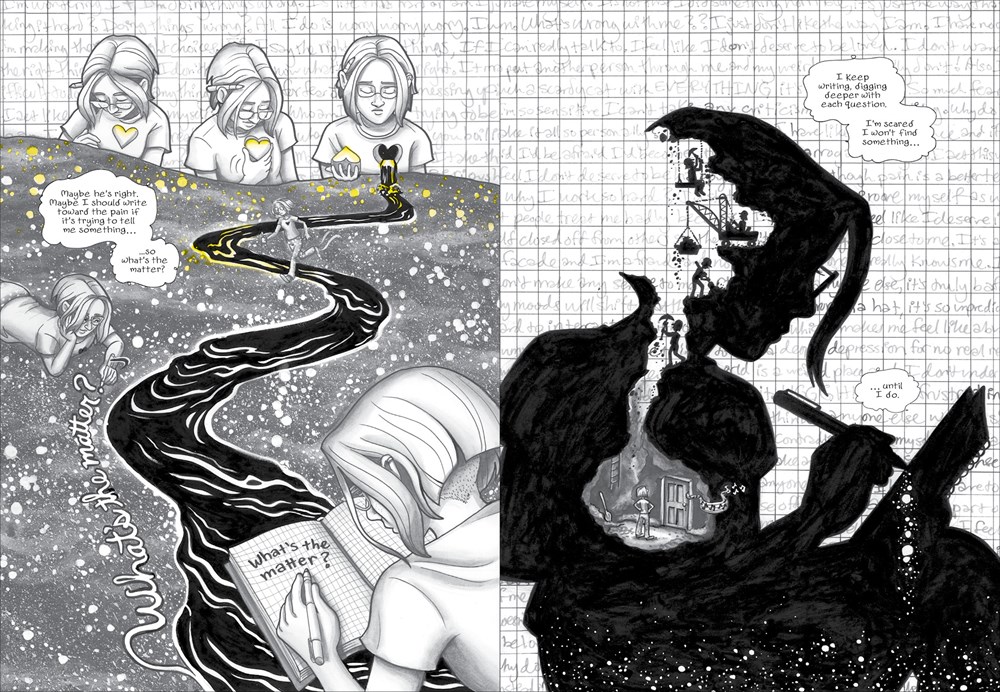

When Mona takes stock of her friendships, she feels like she only has tenuous connections to other people. Mona is a member of the school orchestra, and she has a budding friendship with her chair partner, Aishah, but she sees it only as a relationship of proximity and convenience. When a new girl, Hailey, joins the school and orchestra, her joy and exuberance both inspire and frighten Mona. Though she desperately wants to be her friend, her Matter makes her retreat. I loved the way Gulledge personifies the "Matter" of Mona's depression. Superhero fans might find some comparisons to Marvel's symbiote. It's thick, gooey, and dark, and it pulls at Mona, almost overtaking her at a few points. Mona's battles with her matter are among the most beautiful spreads in the book, and it accentuates Gulledge's versatility as a black and white illustrator.

So Mona retreats, and her depression worsens. She tries to do the right things. She works with her therapist, and she responsibly manages her meds, but those actions only allow her to be essentially functional, and her relationships suffer as a result. Mona's depression shows new improvement, exacerbated by an un-diagnosed physical condition. What this book provides, though, is a map out of this spiral. It is essentially a prescription for a specific type of art therapy. Gulledge coined and championed and term/concept known as "artner," a partner in art with whom one can share and collaborate. She also reminds us to channel those energies into positivity for other people. The more Mona lets other people into her world, the more she is able to see her way through her depression. This book is chock full of lessons for young people to fight through depression, but it also provides great advice for friends and family. Mona would likely not get through her feelings if it weren't for her supportive friends and parents. Aishah and Hailey stick by her, giving her appropriate space, but never giving up on her. It's easy to feel hurt when you're pushed away by a friend, and it takes real work to figure out how to be resilient for other people. That her friends see Mona's value is absolutely crucial. Additionally, Mona's parents listen and understand. They obviously want their daughter to be happy, but they don't force her to be someone she isn't, and they take her feelings serioulsy.

Where we put our focus has a huge impact on how we can feel emotionally. The "Dark Matter" book's title keeps creeping in, and Mona has to actively fight it. She can't ignore it, but she has to come to terms with it. That is the growth for Mona in this book. Following Nash's departure and her perceived flubbing of potential new friendships, her depression has become so dire, so crippling for Mona that she had to personify it to understand it. Now, I should be a little clearer when I use the terms dire and crippling. A wrong interpretation of these words might lend itself to a view of depression and mental health consistent with the reductive stereotypes I decried earlier. It's not as is Mona is unable to leave her house, necessarily suicidal, or at risk of needing in-patient services. When I say "dire," I mean that it looks almost hopeless for Mona to live a life without her "Matter" eating at her. When I say "crippling," I mean that the Matter causes her to withdraw and second guess, hurting her friendships, and exacerbating the cycle of depression as those feelings and the guilt associated with them cause even further withdraw. And shame. One of the elements of depression that is hard to portray is that of shame. And I also think it's one of the harder symptoms for people without depression to grasp. People with depression are often thought of as selfish, and it can be easy to see someone that way, and it frankly might be true for certain people in certain situations. But more often than not, it's unintentional, be it a kind of unavoidable self-sabotage or a type of passive acceptance of the worst possible outcome. What people don't get about those feelings is the level of shame that comes afterwards, and how such a feeling causes a spiraling effect that makes the next apparent selfish action inevitable. Mona bails on her friends because she can't handle their friendship. She doesn't known how to accept it because she feels emotionally bruised. Though she clearly wants their love, she allows what she considers to be a mistake to excuse her from interaction. The shame of this feeling compounds, and Mona doesn't see a way out.

I have to say that I absolutely adored reading this book. Artistically, the use of shade and contrast was incredibly refreshing and engaging. Mona Starr is a black and white comic, outside of flares of color the resemble a yellow highlighter that accent particular scenes. There are different types of black and white comics, of course. There are the increasingly less common black and white books that have to be. There are ones that are look like regular comics, just uncolored. And there are books like Mona Starr that are intentionally black and white, that realize there is something in that nature that makes it meaningful. The artistic heart of Mona Starr is her use of inking vs. shading. There are black and white comics that are heavy on contrast, ones that ultimately don't feel that much different than color comics, the inking almost taking the place of the color. L reserves her inking primarily for thick outlines and leans heavily into shading. The results are some sort of hybrid. Her line-work shows degrees contemporary YA cartoon style - think a more intricate Raina or Hope Larson - but the shading work tempers that style just enough to give it a sort of photorealistic gloss.

Mona Starr is an uplifting book, and not because it takes some Pollyanna approach to depression, but precisely because it tackles it head-on. There is no cure for depression, no real solution. But there are things that make it better, even if it never disappears. In reading about anxiety and depression, trying to both discover how to interpret my own depression and how to mentor my students, whose anxiety is partially generational in its construct and entirely different from my own experiences, almost everyone, from clinical experts to Bill Hader, understands that the only way forward is some willingness to accept the inevitability of these dilemmas, and to lean into them and accept them in order to limit the impact on your own life. And that might be something more palatable for adults, but this is a YA book, and that is a much more challenging quest for a young person who might only be coming to terms with these feelings. Thus, The Dark Matter of Mona Starr, a book that is both sympathetic and direct, one that advises from love and personal experience, belongs in the office of every guidance counselor, clinical therapist, teacher, or psychologist who works with adolescents. It is forgiving without making excuses, informative without being didactic. Lean in to who and what you love.

Laura Lee Gulledge is a teaching artist from Charlottesville, VA. Her graphic novel, The Dark Matter of Mona Starr is published by Amulet Books, a division of Abrams. Her website is full of wonderful resources for Artners, and can be found at www.whoislauralee.com.

![Sweat and Soap [Ase to Sekken] by Kintetsu Yamada](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgMnQltxjWqGS1_duhCp9Er1a0NbALuSFrqvjaV4_PjN_w67xCGghYt-l0qKyqTH7Ei7gbq_mxVq8aPAuOiyaArwAMLJWhpGmOYaARUBnwvjmv2-ZIe20m_zR5CvKnPdI6US_AuOnmi3gSX/w680/57525895-BA7E-4EF8-9FE4-89F9C164E1A4.jpeg)