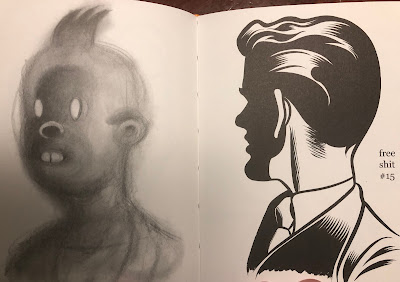

Free Shit

Art by Charles Burns

Published by Fantagraphics Books

Charles Burns has never been a cartoonist who seems squeamish or questioning about this drawings. His work in books like Black Hole or Last Call (reviewed here) dares you to look at it as much as it dares you to look away. He’s a classically beautiful cartoonist whose subjects are mostly disturbing or downright nightmarish. Black Hole, a modern classic, is as alluring as it is horrific. His new art book Free Shit shows us Burns’ desire to find beauty and horror in the same image. That’s what his work shows us, this push and pull between the alluring and the disturbing.

In a lot of ways, Burns is a similar artist to both of the Hernandez Brothers, or at least a cross between them. Like Jaime, he has this classic line that would be perfectly at home drawing old fashioned romance comics as it is at drawing modern tales. But he has a sense of the grotesque like Gilbert, casting his gaze toward the beauty that accompanies the macabre. In Free Shit, more than his comics, there’s even a little Gary Panter that peaks through Burns’ images from time to time, creating these out-of-synch image that are some of the most captivating but puzzling images in this book. While we can see similar traits in Burns’ work to these other cartoonists, Burns drawings reveal more of his vision of the underpinnings of reality. His drawings, whether a portrait of a man who’s looking away from us so all we see is the back of a head mostly obscured by shadow or some ghoulish creature still recognizable as human-like but not human, mold this perception of an other world, of a reality that’s adjacent to ours but corrupted by some physical and mental virus.

Free Shit is a peak into that other world but where in another artists hands we would be repulsed by it, Burns welcomes us into it. In his drawings, there’s practically no separation between the romantic and the grotesque. It helps that there’s no narrative here as our minds are allowed to just take in the images and craft our own stories and world views around them. But Burns doesn’t let us into his work completely unguided and alone. While some of the drawings are rough, pencilled explorations of images and thoughts, a lot of them are finished, inked drawings where Burns’ older and more conservative influences and styles collide with his own unique perceptions of beauty and classicism.

The artwork leads us through this new reality. This is a guidebook to Burns’ search for beauty where the grotesque lives. But with no story to lead us through this art book, there is no judgement of value applied to these images. Andy concept of beauty or ugliness are judgements that we bring to these drawings. What we take away from these images probably say more about our own perceptions and values than they do of Burns’. This book provides a fascinating litmus test about art and they ways that we “read” images.

The disturbing aspects of Burns’ artwork, whether overtly confrontational or more hidden under a non-threatening image, challenge our own perceptions and concepts of what we want to see. Is Burn’s some kind of psycho deviant for drawing these images? But what does it say about us if we can’t turn away from these images, engrossed by Burns’ imagination? These aren’t nice nature drawings; they are pure imagination, showing a different way of perceiving the world around us. Just because it’s shocking and grotesque, that doesn’t mean that it’s not also beautiful. Free Shit challenges us to understand that beautiful and ugly aren’t completely mutually exclusive terms. There’s ways that drawings can be both. Burns’ imagination is full of ugly, hideous creatures but his presentation of them is simply gorgeous and mesmerizing.

![Sweat and Soap [Ase to Sekken] by Kintetsu Yamada](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgMnQltxjWqGS1_duhCp9Er1a0NbALuSFrqvjaV4_PjN_w67xCGghYt-l0qKyqTH7Ei7gbq_mxVq8aPAuOiyaArwAMLJWhpGmOYaARUBnwvjmv2-ZIe20m_zR5CvKnPdI6US_AuOnmi3gSX/w680/57525895-BA7E-4EF8-9FE4-89F9C164E1A4.jpeg)