Written by Christopher Adams

Published by 2D Cloud

Published by 2D Cloud

When I picked up Christopher Adams' Strong Eye Contact, I was immediately intrigued by the idea of creating a silent story about

a stand-up comedian. At the same time however, I was worried based on my

initial scan that it might be too abstract for me to review adequately, as I tend

to gravitate towards more “literal” pieces. I’m glad that I didn’t shy away

from it though, because it really challenged me to leave my comfort zone and

explore a variety of uniquely interwoven themes.

We follow the protagonist, an unnamed immigrant and aspiring

comedian, as he attempts to be, according to Adams, a “typical American”.

Things do not go according to plan though. It’s not as much that he is unfamiliar

with navigating things at the material level (indeed he is very drawn to

material goods as I’ll explore later) or that he is unaccustomed to American folkways.

It’s more so that given the stress of adjusting, his mind becomes cluttered,

leading him to a series of mishaps, such as having accidents and car troubles. The

word ‘burro’ appears on the soft-serve machine he operates as well on the sign

of the pawn shop he visits, suggesting that this must be the name of the area

he lives in. ‘Burro’ is Spanish for donkey, and I believe that it’s a great

word choice as donkeys are often associated with foolishness, an idea that the

protagonist has most likely internalized.

In the first half of the book, each page stands alone as a separate incident, but taken cumulatively, we see the wearing down of the protagonist. Each situation starts off hopeful and ends in some sort of disappointment. His perpetual “failings” are disheartening to both him and most likely the reader, but Adams smartly sets up each situation in a Buster Keaton-esque style, as he mentions, which is vital to lightening the mood of the story and providing some humor.

In the first half of the book, each page stands alone as a separate incident, but taken cumulatively, we see the wearing down of the protagonist. Each situation starts off hopeful and ends in some sort of disappointment. His perpetual “failings” are disheartening to both him and most likely the reader, but Adams smartly sets up each situation in a Buster Keaton-esque style, as he mentions, which is vital to lightening the mood of the story and providing some humor.

|

| Segway troubles |

This piece really explores the idea of what it means to

achieve the “American Dream”. This concept, which has deep historical roots,

suggests that the key to “success” is hard work. It’s an individualistic notion

of “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps” even when the external world

challenges you. And it reinforces the idea that if you are not able to thrive

in this sort of culture, then you are a “failure”. The American Dream also ties

into the idea that if you accumulate money and material things, you will be

happy. Indeed, while many economists

agree that more money equals more satisfaction and have numbers to support it,

others stand by the older Easterlin Paradox, which tenets that beyond a certain

level of income that meets basic needs there is no correlation between personal

income and happiness. Instead, it is RELATIVE income, aka. what is made in

comparison to others, that affects happiness.

So what determines happiness then? The contrast between the protagonist spending a day at the arcade with his family versus him buying a waffle maker for his birthday and eating the waffle ALONE is telling. The former situation is the only time he seems genuinely happy, while each purchase, such as the waffle maker, leaves him unsatisfied.

So what determines happiness then? The contrast between the protagonist spending a day at the arcade with his family versus him buying a waffle maker for his birthday and eating the waffle ALONE is telling. The former situation is the only time he seems genuinely happy, while each purchase, such as the waffle maker, leaves him unsatisfied.

Reading this, I started to think about the documentaries

that I have seen on the Lost Boys of Sudan, including God Grew Tired of Us. The Lost Boys were a group of several

thousand boys who were orphaned and/or displaced due to the Sudanese Civil War

(1983-2005). Enduring unimaginable odds, they fled to refugee camps in Southern

Sudan, Ethiopia, and Kenya. The US government and UN agreed to send a few groups

of them to the US to resettle in different parts of the country. Yes, the two

situations are very different, as No Eye

Contact does not suggest that the protagonist endured any previous trauma

before his emigration, but I thought of it because of how the documentaries

shadowed the same exact process of adjusting to life in the US: striving to

achieve the American Dream through material means despite facing tremendous

isolation and difficulty making a living. Like some of the Lost Boys, we see

the protagonist weather over time due to continued hardship, as reflected artistically

in Adams’ transition from marker to rougher crayons and sparser images.

|

| Adams' crayon work |

The story according to Adams is a “kaleidoscope of

crystalline memory fragments” that tell a larger narrative. Having a seamless

narrative and identity is a human fallacy, so I’m glad to see Adams explore

this. Most of our memory is episodic, yet we link it into the story of us to

make better sense of our experiences and protect ourselves from the fact that

our identity and sense of self are manufactured internally for survival. Comics

inherently play with this idea in the use of panels, but Adams takes it

further, deconstructing linear storytelling and blurring the line between

wakefulness and dreaming.

The last section of the book, which is delineated by yet

another shift in artwork, showcases a style not unlike an unstitched embroidery

grid. I saw each image as a possible future. His environments alternate between

natural, where he seems to thrive (e.g. riding a donkey victoriously through

the desert and playing an acoustic guitar as opposed to his electric one from

the States), and man-made, where he can’t function optimally (e.g. passed out

on a basketball court or bleeding from a car accident).

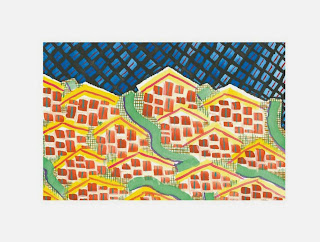

In the first half of his book, Adams intersperses the protagonist’s episodes with abstract marker images of the local scenery which immediately resembled some Australian Aboriginal painting styles to me. At first I tried to decode them in a concrete way, like “Oh, this is Los Angeles” or “This is a cactus in front of a border fence”. Then, upon looking at them more, I started to see landscapes not unlike patchwork quilts or collections of biological processes (e.g. on one page, it looks like red blood cells flowing through capillaries). Despite the fragmented storytelling, there is indeed an integration of different universal elements of life.

In the first half of his book, Adams intersperses the protagonist’s episodes with abstract marker images of the local scenery which immediately resembled some Australian Aboriginal painting styles to me. At first I tried to decode them in a concrete way, like “Oh, this is Los Angeles” or “This is a cactus in front of a border fence”. Then, upon looking at them more, I started to see landscapes not unlike patchwork quilts or collections of biological processes (e.g. on one page, it looks like red blood cells flowing through capillaries). Despite the fragmented storytelling, there is indeed an integration of different universal elements of life.

|

| "Little boxes on the hillside" or skin cells? |

|

| Riding into the... |

After finishing the piece, I returned to the thing that

originally sparked my interest, but in a different light. Why would he choose

to be a stand-up comedian? Adams gives us little indication, as he does not

flash back to reveal his motivations. He

does suggest that the protagonist struggles to make a living, as seen by an

image of his empty bank account in the beginning. Besides the heartache that he

continually experiences to integrate into the dominant culture, his quest to be

a comedian, despite floundering finances or empty crowds humanizes him even

more. He has a passion that gives him life despite the odds, and this is what

matters.