Those who used to read the site regularly know that I have a particular fondness for older comics, partly because I enjoy old things and always have, and partly because in those earlier days there's a total sense of joy and freedom in the work. In some ways, it's a lot like zines and mini-comics in terms of the ethos.

Now it's fairly easy to get ahold of older Batman, of course, and even thinks like Krazy Kat remain accessible. Everyone loves the old EC comics, so much so that multiple publishers put the work out in different formats and collections. But there's such a huge swath of comics that aren't being seen and when I encounter a book like Bungleton Green and the Mystic Commandos, I'm in comics heaven.

Newspaper strips, believe it or not, were always considered a bigger deal than comics, because everyone read the newspaper. And even today, getting a daily strip is a lucrative proposition. So it's no surprise that there are hundreds, possibly even thousands of newspaper strip comics that haven't seen the light of day except when found used as wrapping for a precious antique. Many of them went on for decades, putting out strips that were, to be fair, not particularly notable.

That was likely the case for Bungleton Green, which was started in 1920 for the Chicago Defender by Leslie Rogers and had shuffled along multiple creators when Jackson, a staff artist for the Defender, took over in 1942. The concept was a comical goof who rose and fell in fortunes, effectively a sitcom character on the printed page. Basically, a character I probably would have skipped over back when we had a newspaper subscription or when my grandmother saved the comics pages for me to read because her paper was in color daily, not just Sundays(!).

Upon taking over, Jackson almost immediately pushes the reset button. As comics historian Jeet Heer notes in the introduction to this collection, Jackson, taking inspiration from the now far more popular adventure strips and probably comic books too (Heer specifically calls out Jack Kirby's work), opts to push the main character to the sidelines and bring us the Mystic Commandos. They're a group of kids on a mission, and that mission takes them places no other comics that I know of were trying in 1942. (Hell, it takes them places people today are reluctant to go, as we'll see.)

There's so much going on in these comics it's hard to keep up or try to list everything, and this collection is only a small sampling of the strip. The first arc in this collection is a wild trip. A young man Green knows is framed and to save him, we get the involvement of Prince Whipple, George Washington's oarsman when crossing the Delaware, who takes two punks on a trip to visit the first president in an attempt to help them learn honesty. When that doesn't work, in a Fletcher Hanks Special, Benedict Arnold, now a demon of Fireland(!), scoops them up and briefly tortures them into telling the truth.

(If half of you reading this aren't pausing at this point to go track this book down based on that last sentence alone, I am not doing my job and should re-retire.)

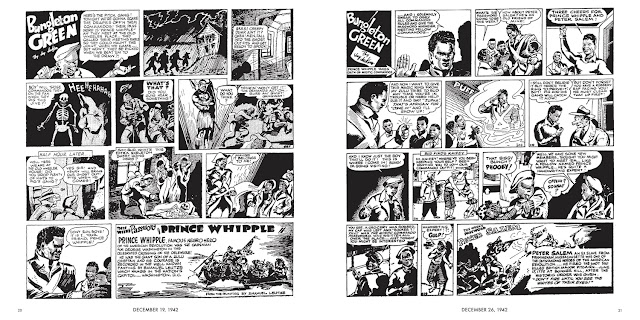

Jackson's imaginative ideas would be enough to carry this into must-read territory for me on the premises alone. But now let's take a moment to discuss the art. Here's the introduction to Prince Whipple's entry into the strip:

Look at how much is going on in those panels! It's an artistic clinic. What especially stands out is the stark difference between the inherited character of Green (check him out on the second page, 7th panel) and everything around Green. Jackson refuses to limit himself to what has come before and immediately puts this strip on a par with its better known white newspaper peers. In fact, if anything, he goes further. While many comic strips of this era are just as well drawn, but stiff, Jackson's characters move in a way that others don't. They looks as if they're always being caught in the act of doing something. It's what Stan Lee would call out alongside John Buscema in How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way. There's a huge difference between drawing a scene and making it come to life. Jackson had that ability and it shows, page after page.

The panels above give a great example of what I'm referring to. First we get a punk discussing his plans. In a lot of comics, even those published today, this would be a straight-on look in a static pose. But instead, Jackson angles his cap to help offset the title of the strip. Then he uses the character's hands to give us an idea of his arrogance. He's pointing back at himself in a boast, then extending the other hand outward, leading the reader's eyes to the impending story (that doesn't go well for him!). His face has a perfect set of menacing eyebrows and a wide mouth, ready to tell you how awesome he is.

And that's just the first panel, folks!

Moving down the page, we follow the action, from the terrified punks who get a neat hat-raising moment to the Commandos who lean forward to grab items and can clearly be seen to be reacting to the appearance of Whipple. The second page sets up the mystical aspects of the strip and shows further how different the good kids are from the bad ones. Look at how as part of the exposition, we see Knifey pulling a poor girl's hair and stealing her candy while he disses the whole idea of the Commandos. We of course know from what's come before and in his speech what a bad person he is, but comics is a visual medium and Jackson recognizes this early and often. We're going to be able to see as well as read what's happening.

"That's great Rob, but what about Demon Benedict Arnold?"

Okay, okay, I'll show you that page, too, though I had to take a picture of it so the quality isn't as good:

If Hanks ever saw this page, which is sadly unlikely, he would have been grinning from ear to ear.

From this arc, the collection moves into Jackson's take on the war. He does an amazing job of linking Nazi views to racism and attempts to disunify America (and therefore hinder the war effort) by stoking the fires of racism and division. The more things change...

That arc is a fairly straightforward one, and then we start getting really strange. The Commandos find themselves in Germany, and the only way to escape is to let an old white guy "kill" them then go back into the past. Which of course means that Jackson gets to deal with the issue of slavery and its legacy head-on while using science fiction as his (very thin) cover to do so.

Here's the second page from that arc, again with apologies for the scan:

While this is set in 1778, it could easily portray events of any point in the twentieth century, and Jackson (along with his readers) would have easily recognized this. The depiction of the whipping is so striking and horrifying, and the look of the mob is nothing but vile hatred. I love how Jackson shows their intensity and you can almost see them moving because of the way he draws their hair rippling as they rush to attack the Commandos for saving one of their own. As with the earlier pages, the dynamic action of the figures shines, page in and page out.

By this point, Green himself is looking really out place. He shows up less and less as we move from the past to the future of 2043.

Check Green making a cameo in the fifth panel like he's Shermie in a Peanuts group shot in the 1970s. Also kinda interesting to see how Jackson was ahead of his time, predicting that Florida would be devasted by an ecological disaster! This arc introduces a race of green men dedicated to ruining the Utopia and gives Jackson a chance to further expand his worldbuilding. He never stops hammering on the evils of racism, either. During this part of the strip, the Commandos encounter a world in which white people are the hated minority and we get scenes about being unable to work, unable to talk to women of a different color, and other things being experienced by Jackson's readers at the time.

I type "at the time" but let's be frank. A lot of what Jackson is depicting can and still does happen here in the United States and elsewhere in 2024, less than 20 years from the Floridaless Utopia shown above. That's as plain as the ridiculous nose on Green's face. I cannot and will not know how the lived experience of Jackson, his readers at the time, or readers of color now impact on these comics. What I can state with certainty is these are amazing drawings from a creator who needs to be more widely known and do my best to make that happen by calling attention to Jackson and this collection.

That arc ends hopefully, and I'll share it here to remind us all there's a chance if we don't give up on the possibility of a better world:

I'll also quickly note that even on a talk-heavy page like this, by having characters playing, gesturing with their hands, leaning to see the action, and other little touches, Jackson keeps the reader's eyes engaged while providing an upbeat ending. I'd also like to spotlight how great his use of black ink and shadow is here. Again, not to be too harsh on modern artists, but I feel like a lot of this art has been lost. You can do so much to make a page come alive just by adding some extra ink.

The last panel is a great spotlight on poor Green, who loves the era but is feeling out of place. He's been shunted to the sidelines of his own comic strip, but the final story in the collection changes that. After a little bit of very modern meta commentary on how silly he is in terms of his depiction compared to everyone else in the strip, Bungleton Green literally gets remade into a super powered robot(!):

Brilliant! Just sheer genius on the part of Jackson to use his science fiction conceits to try and find a way to make Green less out of place, but with the added bonus of getting to do more commentary about how some who wanted to "improve" black people were just trying to find a new way to enslave them. It's a layering almost as complex as the artwork here, which further develops Jackson's experimentation with black ink and shadow. He's also working the angles (literally). On that first page, feast your eyes on just how many shifts there are in how the characters are viewing the action. We bob and weave as the reader right along with them. While there is yet again a lot of talking going on, there is plenty to focus on. Then on the second page, the action of the conflict is so vivid, I can almost trick my eye in making the third panel move and watch at the invigorated Green shakes the other man and shouts "I want to be FREE!"

Just perfect scripting here. That whole sequence gives me chills every time I read it.

That's the end of the collection, which ends with a series of historical one-panels that Jackson included, one of which you can see in the first set of images above. Green's transformation into a superhero (probably the first black one, to boot) takes him so far from the kindly man helping a set of kids that we see at the beginning. Jackson has made this strip, which would go on past his death and last until 1964, really and truly his own.

Bungleton Green and the Mystic Commandos hits on so many levels. It's a work of civil rights. It's a historical artifact. It's an artistic masterpiece in an era where a lot of the art - even from the key figures of the time like Simon, Kirby, Kane, and Falk - doesn't always hold up to a modern eye. But perhaps most importantly, the stories themselves feel just as fresh today as they did when they were published, and not just because some of the plot points are sadly all still too real today. A historical figure coming to the rescue of a wronged teen, stopping spies, time travel, utopian worlds rocked by those who would rule them - these are all timeless ideas and concepts which Jackson plots as deftly as anyone else who's tried.

Sometimes I read historical comics for the historical value. That's where I started with Bungleton Green, but it quickly because far more. You can hand this book to anyone who loves science fiction and fantasy and they'll have a blast. My only wish is that we get a run of Jackson's work, just as we have for his white peers. We need someone to reprint these in full (if they are available) in nice hardcovers, like they've done for Prince Valiant, Popeye, The Phantom, and so many others. To leave Jackson to semi-obscurity is an injustice. I'm so glad NYRC published this collection and I would highly recommend you track down a copy for yourselves. Let's get this series into the conversation about classic comic strips. It's well deserved and far overdue.