Mike's Favorite Comics of 2019

I would like to dedicate this list to Anne Arundel County Public Library and its wonderful staff. Many books on this list and my 2019 reading pile as a whole came from the library. Our county library has afforded me the opportunity to read many more books than I would have the opportunity to do without them. I've tagged the books I include from my library to highlight its impact on my reading this year. Get yourself a library card if you don't already have one!

Book of the Year

Clyde Fans

Clyde Fans

by Seth

Drawn and Quarterly

Library Book

I was utterly mesmerized while reading this book, and I would have finished it in a single sitting had I not started it at ten o’clock at night. Clyde Fans is a tale of the breakdown of the (North) American dream, of the broken promises of mid-century Canada, of the failure of post-war optimism as the decades clicked past. But it’s also a story of family, specifically two brothers Abe and Simon. Abe is arrogant and self-assured if somewhat depressed, even during his decline. He is a classic anti-hero, and he recalls the hamartia of Greek tragic heroes. He’s somewhat abrasive and ultimately unlikable, but he is also the lens through which we see much of the story unfold. Simon is equally frustrating and frustrated, suffering from both crippling social anxiety and a lack of support from his boisterous brother. The book functions as a meditation on privilege, namely how well one can succeed in the Western world if you are born into privilege. The decline of the Clyde Fans business is by no means sudden, and even the less-than-reflective Abe can pinpoint mistakes. That he shrugs it all off speaks exactly to the level of privilege that blinded him.

Stylistically, Clyde Fans is almost monochrome, told through hues of blue, black, and gray. The pages manage to be both subtle and crisp, and Seth’s Canadian landscapes, alternatively fertile and sparse, are one of the major benefactors of the color scheme. The book itself is an unintentional study on style. Seth himself comments in the afterword on the stark contrast between his drawings from the beginning to the end of the book, and it’s something I didn’t notice upon first read. Seth’s drawings at the onset – 1999, mind you – are wavier, less geometric. His panels are larger panes, and he makes use of the surrounding setting much more. By the end of the book, his style has coalesced into a more intricate and novel panel structure, preferring small drawings and a more geometric pattern. I hesitate to say that Seth progresses from Fauvist to Cubist, but there is something in the change from waves to forms that is striking upon second read. That this change occurs gradually and reflects the dynamic progression of Abe and Simon is one of those unintentional Easter eggs resultant of genius.

Superhero Book of the Year

Superman Smashes the Klan

Superman Smashes the Klan

by Gene Luen Yang and Gurihiru

DC Comics

Gene Yang captures a voice for Superman better than any creator over the past decade. The original announcement for Superman Smashes the Klan indicated it was part of DC’s new imprints for young readers and young adults, but this book carries no specific designation. And that’s good, because frankly, it is neither a kid book nor an adult book. It’s a Superman story. For all readers. Based on a Superman radio serial in the 1940s, Superman Smashes the Klan is a story that returns the big blue Boy Scout to his roots as a champion of the underdog. It speaks to the very nature of who Superman is and why he is a symbol, himself an immigrant who fights isolation and xenophobia in the name of unity. Yang and Gurihiru studios capture the tone of the animated series, the idealistic Superman of the late thirties, early forties, a Superman who legitimately and un-ironically believed in the power of the American Dream: incorruptible and powerful, but grounded and gentle all the while. More than anything else, Yang reminds us that Superman is at his best when he is the beacon of hope for the oppressed and downtrodden. Superman stories peak when they are about real world implications and injustices, when they inspire us to find the little bit of Clark that lives inside all of us.

Are You Listening

by Tillie Walden

First Second

*Library Book*

Tillie Walden’s Are You Listening is a superb coming of age story set as against what becomes a surreal road trip. Visually, Walden's book is one of the best looking of the year. This lady can draw a sunset. Beautiful tones make this book, and Walden ties the emotional weight of the story in perfectly with her absolutely fantastic use of color and shade. Eventually, the book gets surreal, and it’s a sudden, unexpected change, but it feels far more gradual in Walden’s hands. There’s no gap, no herky-jerky feel. Sometimes such tonal or setting shifts can feel forced, but not in Are You Listening, mostly because Walden’s beautiful, flowy art can handle that shift with ease. Walden also works the narrative with a careful pen. Bea’s transformation, and ultimately her acceptance via vocalization of who she is, proceeds gradually and naturally. Lou’s guidance as a sort of Gen X fairy godmother of sorts, is perfectly paced. Are You Listening is a book packed with sincerity, answering the big questions of adolescence, urging the reader to find themselves and to escape the life others have decided you will live.

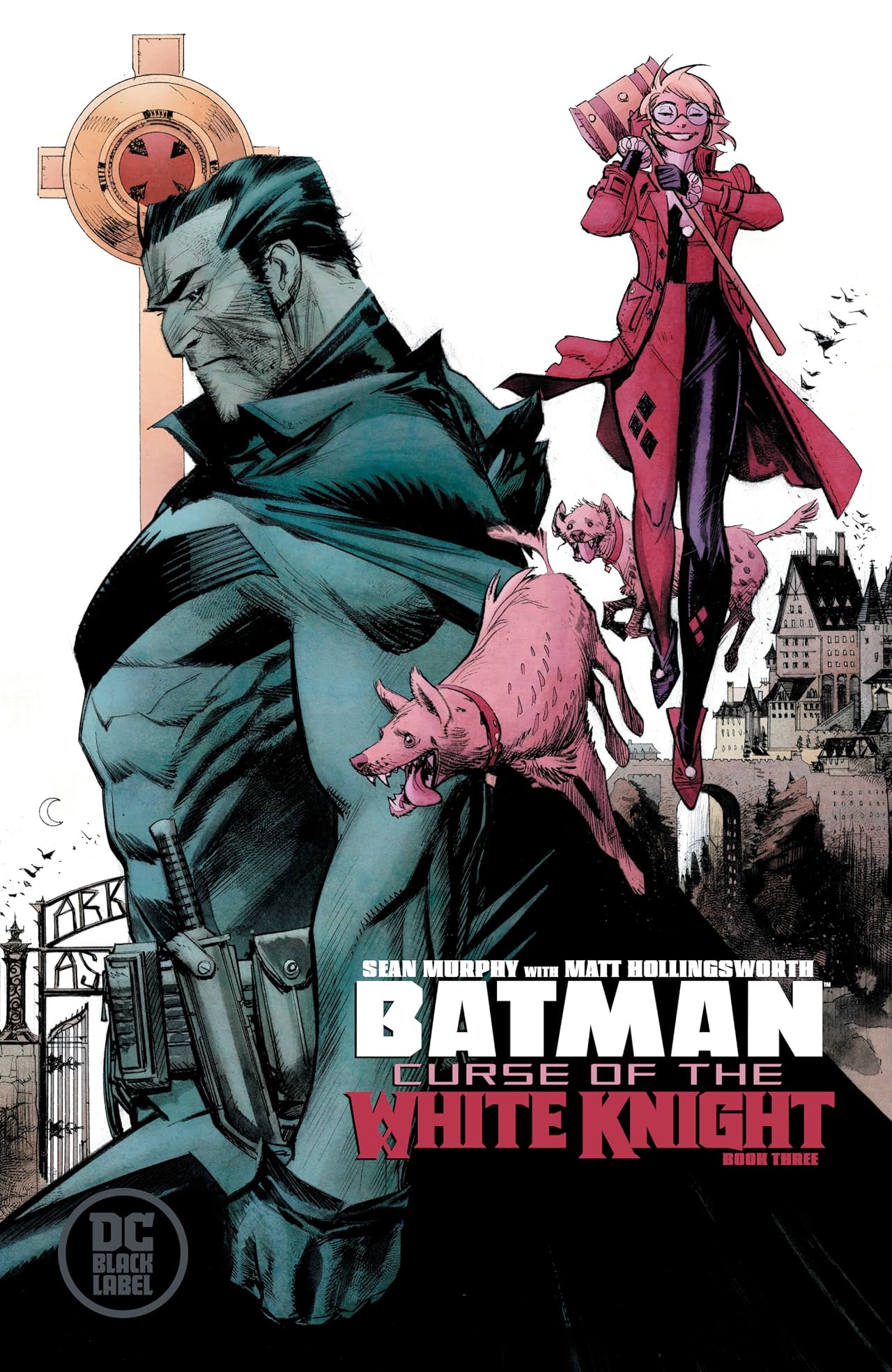

Batman: Curse of the White Knight

by Sean Gordon Murphy with Matt Hollingsworth

DC Black Label

Murphy’s Batman, and by extension, his Bat-verse, is my favorite current incarnation of the Dark Knight. It’s indebted to so much of what formed my Batman worldview – The Dark Knight Returns, The 1989 Batman film, and the 90s Moench/Jones – that it feels both novel and nostalgic.Murphy's take is a re-distillation of Batman – a little more real world without being overly “grim and gritty,” while managing a ton of character development for a mini-series. Curse of the White Knight is big storytelling at a cinematic pace, a new model of the widescreen action of the late 90s, a widescreen realism of sorts. Murphy’s details are hyper-specific while his nods to canon are understood on face. In this volume, he imagines a new kind of Azrael, another test of Batman’s purity after the Joker/Jack Napier caused the entire city to question everything they had assumed about Batman’s role in their lives.

Batman: The Last Knight on Earth

by Scott Snyder, Greg Capullo,

Jonathan Glapion, and FCO Plascencia

DC Black Label

The world of Last Knight is a post-apocalyptic landscape featuring familiar yet changed versions of our favorite heroes and villains. if that feels a little Old Man Logan-y, fine. But he whole concept is novel, though, for Snyder and Capullo, whose Batman work has been primarily grounded in the Dark Knight as an urban vigilante. Prior to Snyder’s Justice League work, we hadn’t seen him do an off-the-wall sci-fi story, but this book is much more in that vein. It’s a little pulpy (in a good way), and dark without being macabre. And while there are certain Old Man Logan connections (if not allusions), the premise for Last Knight is an intriguing one. It isn’t that evil ultimately won, or that the heroes were somehow compromised and exposed. Yes, the world of Last Knight does arise because the heroes failed, but it seems like the heroes failed more in the abstract than in action. As we get through issue two, Batman attempts to navigate this new terrain in an attempt not only to correct whatever has gone wrong, but also to understand his place as a hero, if he still has one.

BTTM FDRS

by Ezra Claytan Daniels and Ben Passmore

Fantagraphics

*Library Book*

What do you get when you combine the creator of the spectacular Upgrade Soul with the cartoonist behind Your Black Friend? A sci-fi horror satire of gentrification and hipster culture. Daniels and Passmore have both waded into this territory before, but even more so than previous works, BTTM FDRS provokes big questions about the social constructs that surround alleged urban renewal and the sanctity of neighborhoods. Who owns what? Who has a right to live somewhere? It’s easy to love a book that resonates with you personally, and the issue of gentrification has always nagged at my consciousness. In BTTM FDRS, our main character, Darla, finds herself returning to the fictionalized Bottomyards, her brief childhood home. She is herself caught in some limbo between the original residents, early migrating urban bohemians, and new arrival hipsters looking for precious authenticity. There is a great scene involving Darla sitting at a bar with her new friend Julio, a rapping Pilgrim MC named Plymouth Rock, in which she questions whether anyone indeed has the right to live in their neighborhood. And that’s the tone the book strikes on gentrification. It is a satire, of course, but it by no means a manifesto and certainly not a rulebook. Passmore and Daniels are content with asking the kind of probing questions that drive a real conversation. As they make that point, the book dives head on into its third act, and the sci-fi horror ramps up. And Darla and company have to wrestle with an even deeper metaphorical dilemma?. Does a monster deserve to inhabit a building if it has always been there?

Cannabis - The Illegalization of Weed in America

by Box Brown

First Second

*Library Book*

Brian "Box" Brown has the perfect style for the world of informational graphic novels. It's clean and bright, allowing the reader to draw attention to the important details and to understand complex ones with more acuity. Few topics are simultaneously more straightforward yet incredibly complex thank the US cannabis policy - straightforward in the aversion, utterly complex if not ridiculous in methods to ensure prohibition. But Brown is able to simplify this process and provide a wide angle take on the entire issue that provides insight and introspection. He presents his argument in such a way that it is not alienating or demeaning to a differing opinion. Like all of Brown's previous offerings, Cannabis - The Illegalization of Weed in America is a exemplar for teaching through sequential art.

Creation

by Sylvia Nickerson

Drawn and Quarterly

*Library Book*

There are a number of great experimental books this year that play with either form or structure to provide a new experience. Nickerson’s Creation is non-linear and a little stream of consciousness, but it’s how she plays with illustrations that makes this book unique. People are formless, but recognizable – think the Ped X-ing sign or the AOL Instant Messenger mascot. Her inking is deliberate, just enough to provide contrast between big items. Most of the book, though, is pencil shaded without any inking, and thus it takes on a sketchbook effect. Nickerson paints an even bleaker picture of modern Canada, specifically Hamilton, and the perils of alienation. She contrasts the dread of loneliness with the burden of motherhood – one is entirely isolated almost by the fact that they’ve managed to create a life and bond with it permanently. Creation is also the story of generations, of what created Sylvia herself, all the layers and reflections of memories that make up one person come to the forefront for a reckoning. The result is a book that is sharp and clean, but also very thoughtful.

Die

by Kieron Gillen, Stephanie Hans, and Clayton Cowles

Image Comics

What if it were possible to get lost in the game? What is my mother was right, and AD&D was actually a Satanic ritual? What if dungeon masters were really tinkering with a rift between worlds? Such is the premise of Die, a book that is part Jumanji and part Lord of the Rings. The story is fundamentally a mystery, and it deals with loss and regret in very tangible ways. Gillen provokes big questions about how the games in our lives define us, and he opens up big wounds via a dark fantasy landscape. His narrative is certainly intriguing, but Die is more of a celebration of Stephanie Hans' incredible art. Somewhere between impressionistic oil painting and photo-realism, Hans plays with tones and shades, and invokes all modes of light to a near devastating effect.

East of West

by Jonathan Hickman, Nick Dragotta, and Laura Martin

published by Image Comics

Much to our chagrin, East of West is but an issue away from its finale. It's always hard to end a story, but the march to the finish has been classic Hickman. The world he and Dragotta have created is one of the great achievements in science-fiction storyelling, blending tropes of both space opera and cyberpunk and the genres they ape, namely the western and the noir. My favorite thing about Hickman books is his exceptional ability to envision worlds that draw from our own build reflect far differently. Such is the crux of the last year of East of West. Mysteries unravel while the big concepts Hickman has teased since the first issue coalesce into a new status quo as the apocalypse that presaged armageddon forces the characters to march on towards inevitable doom.

Giant Days

by John Allison, Max Sarin, and Whitney Cogar

BOOM! Box

The final year of Giant Days reminds readers why they fell in love with the series to start. In this last year, we’ve felt this story coalesce into a full rendering of the early adult experience – that transition time between being an adolescent and an actual adult, the late teens-to-early 20s period in life where we all end up finding out who we were supposed to be. Giant Days does this with humor and heart. This book is funny. It both laughs at itself (or its characters) and the world around it. Most uniquely, it’s sardonic without being sarcastic. The relationships are real, and the emotions between them pour of the page. I especially loved the 50th issue both as a standalone and as the lead up to the final arc. The contrasting goofiness of the ladies subbing in last minute in a cricket match with the tragic news McGraw discovers was somber without feeling melodramatic. The ability to enter the hearts of readers and pull from an entire range of emotions is exactly why Giant Days will grace the trade shelves of comic shops, book stores, and libraries for years to come.

Gideon Falls by

Jeff Lemire, Andrea Sorrentino, and Dave Stewart

Image Comics

In the second year of Gideon Falls, Lemire and Sorrentino start pulling at the threads of the mystery they built in the first arc. It’s hard to imagine that this book has only been around for 18 issues. The beginning of this year saw the Original Sins arc come to a close, revealing some of the mystery of the Black Barn, the town of Gideon Falls, and the life of Norton Sinclair. It’s almost painful to write about this series while avoiding spoilers. In the third arc, Lemire jumps head first into the world opened by the Black Barn, and Gideon Falls warps from creepily mysterious horror series to science-fiction thriller. These revelations are a real gift. It’s easy to assume that some of the luster has worn off as the bigger secrets play out, but Lemire continues to build a complex web, adding layers to the nature of the Black Barn. Playing with a multiverse, playing with time, heck, playing with reality – there is still plenty of guesswork here for the reader. So much writing has developed into cheap misdirection coupled with supposedly shocking reveals. But that isn’t the case for Gideon Falls. Lemire clearly works some magic with this plot, but he’s brought to new heights with his frequent collaborator, Andrea Sorrentino. Since I, Vampire, Sorrentino has been gradually refining his approach, continually playing with fraying edges and line structures to develop an approach that amounts to a layer of contrasts. A combination of Jae Lee and J.H. Williams, his work is simultaneously atmospheric and gritty. Dave Stewart’s color work elevated Sorrentino’s linework even higher. His palette is one of contrasts, and it lets Sorrentino’s lines and shades shine.

Glenn Ganges - The River at Night

by Kevin Huizenga

Drawn and Quarterly

*Library Book*

Perhaps no book looked better on its paper stock than Huizenga's Ganges collection, the culmination of nearly a decade and a half of comics starring the titular hero who is part Walter Mitty, part Don Quixote. A book like The River at Night is a manifesto for reading physical copies if there ever was one. Sepias, blacks, and blues cover Huizenga's pages on richly textured matte pages, thick and almost magazine-sized. Each page is rich and expansive. Huizenga plots masterfully, alternating between panel size and cramming content onto the page without making it ever feel crowded. Glenn Ganges is a wonderful character, a great pair of eyes through which to view the world. He is thoughtful and introspective, and Huizenga's exploration of his mind and subconscious provides an incredibly entertaining read. It is remarkably easy to get lost in Glenn's thoughts after he himself has ventured down his own subliminal rabbit hole.

Harleen

by Stepjan Sejic

DC Black Label

I cannot overstate how surprised I was by the first issue of this mini-series. I’ve found Harley to be an over-used character who has easily become a caricature of herself. My Harley has always been Jester Harley of the Animated Series and derivations that stick within that tone. Hot Topic Harley has never been my cup of tea, and I wasn’t particularly looking forward to trying a mature readers take on her origin because I was sure it would be self-indulgent.

No, this isn’t my Harley, and yes, this is a serious, mature take on her character. However, the angle Sejic takes in this series is far more psychological and meditative that I could have imagined. Instead of lunging into a depraved whirlwind, Sejic paints a picture of intrigue. His Harley doesn’t appear particularly corruptible. She isn’t depraved; there is no particular dark side. She’s smart and thoughtful, and that may very well be her downfall.

Sejic is perhaps most famous for his painted covers and photorealistic Top Cow books. His art for Harleen is in that same photorealism realm, but it’s deliberately less refined. His lines are sharper; his colors are muted. Sejic has always played with light in his work, and his focus on the near absence of it in this book complements the tone nicely.

Hot Comb

by Ebony Flowers

Drawn and Quarterly

*Library Book*

This is another book that connects personally with me because Dr. Flowers grew up close to where I live and work, and the stories she tells remind me of my students. Hot Comb is a reflection on youth through the lens of black hair. For our kids, hair is a very important aspect of style and personality, and that idea is infinitely magnified for a black female, who may have to endure a painstaking regimen to feel confident as a young lady amidst the shark tank that is the school playground. Flowers, who is a first time graphic novelist and a relative newcomer to cartooning as a whole, offers us touching stories of youth and revelation. Her stories aren’t about anything necessarily large, but they feel infinite in their scope. Hot Comb is certainly about the hardships of growing up, and it uses the metaphor of hair – hair that needs to be greased and pulled and ironed and treated – to drive home this theme. But more so than that, it’s a book about understanding the world around, learning those little lessons that come with age, or finally growing old enough to understand adults’ secrets. Flowers’s illustrations are free flowing and natural, and in both her art and tone, Flowers recalls Lynda Barry, who blurbs this book and is the godmother of this entire subgenre. Flowers creates more refined satiric magazine-style adverts to act as separators between each story. They’re funny enough, but they also stand as a start contrast to her more playful, immediate style of her panel work.

There is a great amount to relate to in this book, regardless of one’s background. But certainly, this book is yet another great ambassador of its culture and message, marrying the pains of growing up with the specific trials and tribulations unique of hairstyles. Black hair functions as both a plot point and a metaphor. It’s easy to misunderstand, and it’s especially easy for people outside the culture to take for granted. Don’t touch black people’s hair. Especially lady’s hair. To be fair, don’t really touch anybody’s hair. As a bald man with a shaved head, I can relate to this phenomenon as many people still find the need to rub or pat my head. Though, one of my favorite moments as an educator is when, while reading aloud to students, I looked up and there seated in the back of the room were two girls, one white and one black, each one playing with the other’s hair. The white girl curled the black girl’s hair around her finger before letting it pop off and starting again. The black girl ran her fingers through the white girl’s long hair, pausing every so often to deposit the loose strands onto the floor. Who knows how hard either girl worked that morning for their do, but in that moment they seemed like one. Hot Comb brought that memory back for me.

House of X/Powers of X

by Jonathan Hickman, Pepe Laraz,

R.B. Silva, and Marte Gracia

Marvel Comics

There is almost nothing better for a superhero comics fan than when X-Men comics are good. Somewhere around the end of the first volume of Uncanny, as the events of Schism took hold, the X-men stopped being about the long-form, operatic storytelling that had come to define them. There were seemingly endless reboots and resurrections, and everything felt like it had been done before. There have been good series in there: Gillen’s Uncanny, Taylor’s X-Men: Red, and Rosenberg’s Uncanny, among others. But it never felt like the franchise as a whole was firing.

And then Hickman joined the fray. His leadership of the X-books as a subset of the greater Marvel publishing catalogue is proof that these books need some sort of captain at the helm. All things X need to point in the same direction. Hickman brought a brand new component to the X-world, one that seemed to elude the mutants for any extended period of time over their fifty-plus years of history. He let them win. The X-Men currently operate from a point of extant power, and thus the dynamic is entirely different. How Hickman continues to explore this effect on the characters will ultimately define the run, but he’s already managed to re-invent Moira MacTaggart, create a new mutant nation using Krakoa, answered the question about endless death and rebirths, and united all mutants under a single banner. Now, the treat will be watching it fall apart.

Immortal Hulk

by Al Ewing, Joe Bennett, Ruy Jose,

Paul Mounts, and Cory Petit

Marvel Comics

*Started Reading As Library Book*

Prior to picking up the first trade of Immortal Hulk, I had never read a single issue of a Hulk comic.I knew the character both from years of following comics and I had, of course, read books with the Hulk in them, just not a book of the Hulk on his own. So, coming into Immortal, I was admittedly nervous. How much backstory would I need? How much of this character’s psyche did I need to absorb, and how quickly? I knew the Hulk was more than a smashing brawler, but I also know that the Hulk was precisely a smashing brawler . . . So, how would I fare?

Pretty well, I think. I know I’m not the first person to say it, but Immortal Hulk is as much a horror book as it is a Hulk story. It is a wild examination of the self, a thorough gaze into the abyss of existence and the nature of one’s own position in it. Ewing poses the fundamental question: what does it mean to die? using a character who seemingly can’t, or possibly won’t. One of the real treats of this series is Ewing’s pacing. His reveals are slow and exact. They are almost predictable in hindsight, and I’ve always thought that trick is a mark of a good writer. As a result, this book is hard to wear out, even after 27 issues mining the same central conceit. Dualism seems to be a defining theme for a character like the Hulk, but Ewing takes everything we knew about the Hulk and puts it through a kaleidoscope of ideas. The Hulk isn’t just another version of Banner, he is of another world.

The Life of Captain Marvel

by Margaret Stohl, Carlos Pacheco,

Marguerite Sauvage, Marco Menyz,

Rafael Fonteriz, and Clayton Cowles

Marvel Comics

*Library Book*

Captain Marvel had a pretty good year, from the remarkably successful movie to a strong series from Kelly Thompson. Life of Captain Marvel, though, makes it onto my list here because it is a heartfelt reworking of Carol Danvers’ origin. The book gives us a sense of who Carol is, and, more importantly, who she is meant to be. There is a beautiful contrast at work throughout the book – while Carol is arguably the most powerful Avenger, she’s not capable of fixing her family situation. She isn’t able to reconcile her father into her life, nor is she even able to grieve. She can’t figure out her brother, let alone save him from a near-fatal car accident. And, like many people, she just can’t seem to get on the same page as a her mom. To some degree, this is the fundamental Superman/Clark Kent dichotomy, but it also works well for Carol, and it gives her some grounding. A special bonus with this story is Marguerite Sauvage’s artwork in the flashback scenes that pepper the book. Sauvage so rarely does interiors, it’s a special event itself.

Little Bird

Darcy Van Poelgeest, Ian Bertram,

Matt Hollingsworth, Aditya Bidikar, and Ben Didier published by Image Comics

Little Bird is a great testament to the vitality of the serialized issue for the sheer nature of suspenseful storytelling. I was on the edge of my seat reading this series, and I anxiously awaited each next issue. Van Poelgeest's story is as wild as Ian Bertram's sinewy and funky bio-punk influenced artwork. The story is a little on the nose in terms of one savior rising up against a dictatorial regime, but it casts a new set of characters, namely First Nations people against an even more repressive version of a corporatized Catholic Church. There is a ton of movement in this story, and the pacing feels like that of a film, not surprising given Van Poelgeest's resume. The shining stars, though, are Hollingsworth and Bertram's panels. I've always been impressed by colorists who adapt to their pencil partner, and Matt Hollingsworth is as good an example of that skill as anyone. Bertram's art is hyper-detailed and bouncy. There is an entire emergent world of unique twists and juts at the end of Bertram's pencils, and it would be easy to get lost or muddled. Hollingsworth does more than make the line work shine, he adds a different dimension.

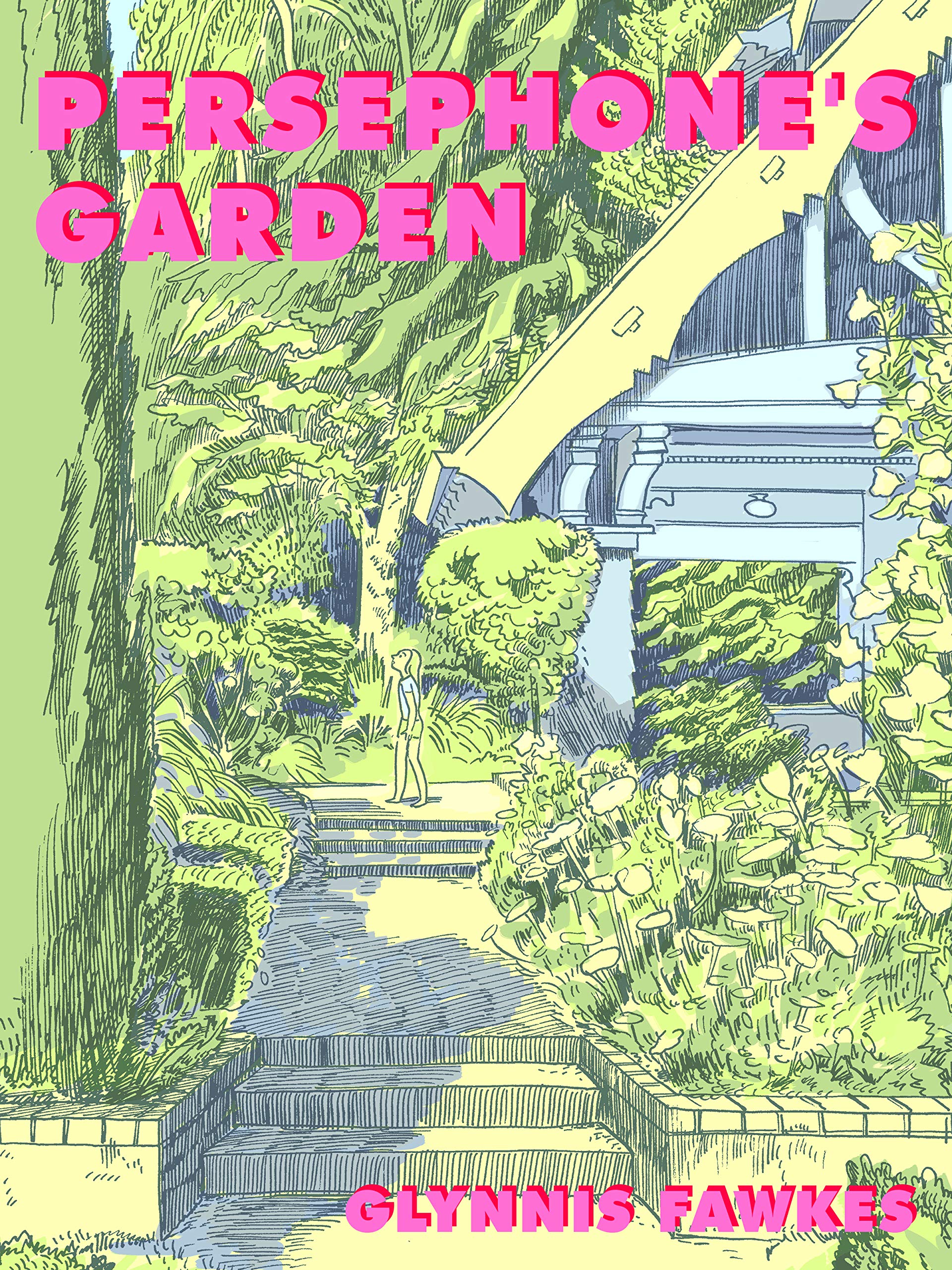

Persephone’s Garden

by Glynnis Fawkes

Secret Acres

I don’t know if I’ve been more charmed by a book in quite some time. Glynnis Fawke’s Persephone’s Garden is actually a compilation, a sketchbook diary that functions as a kind of graphic memoir when fully assembled. The composition of this book is a delight. We get to witness a progression of styles based both on necessity and choice. Some pages feature intricate designs, while others are quick drawings that capture brief moments incredibly well. To have capture them another way would likely have lost the heart of those moments. It is such a beautiful book because it isn’t overthought; it has a gift in that it wasn’t actually composed to be what it is. It’s a true diary, not a memoir. A collection of life, it functions as a natural reflection on raising kids in settings that are fairly unique, such as an archeological dig in Cyprus, but with universal situations like temper tantrums over stopping for ice cream. The real beauty of this book is towards the end where both Fawkes art and narrative seem to refine and coalesce. Her children are older, but the trials don’t evaporate. She channels the mother-daughter relationship as well as I’ve seen in any form, the simultaneous “pay attention to me get away from me” vibe of adolescence captured nearly perfectly on the page.

The Terrifics

by Gene Luen Yang, Steven Segovia,

Brendan McCarthy, and Protobunker

published by DC Comics

The promise of the “New Age of Heroes” brand was two-fold – re-imagining Marvel heroes in a DC context and placing artists first as the creative force behind a book. The Terrifics stood out in a few ways in that it had one of the highest profile writers the comics attached and that it also used current DC characters instead of new creations. The Terrifics was supposed to be DC’s answer to the Fantastic Four who, when this series was announced, were still in Marvel Universe limbo. Literally. Allegedly, the concept from Lemire’s Terrifics run was based on his Fantastic Four pitch. The series struggled as a result of changing artists and a storyline based on an event series that hadn’t exactly ended. After Lemire finished the first two arcs and left the book, I was stunned that it stayed going, but I was absolutely delighted to see that Gene Yang would be taking over the book. Under Yang and Segovia, the book has been what it originally promised to be. It’s often said that the Fantastic Four aren’t a team of superheroes; they are a family of adventurers, and Yang’s Terrifics become just that. Yang built on Lemire’s foundation and brought the team together as a group that has grown into a unit, and one that is tackling the big idea concepts we’d expect from Silver Age Kirby/Lee Fantastic Four stories. Segovia’s artwork is clean and bright, exactly what you’d want from a book with this tone. Yang has found a great voice for Mr. Terrific, softening some of his previous Terrifics characterization and finding a more human voice for him. He’s brought in more backstory for Plastic Man, added depth to Phantom Girl, and made Metamorpho a little more multi-dimensional. This is my favorite monthly superhero series being published right now.

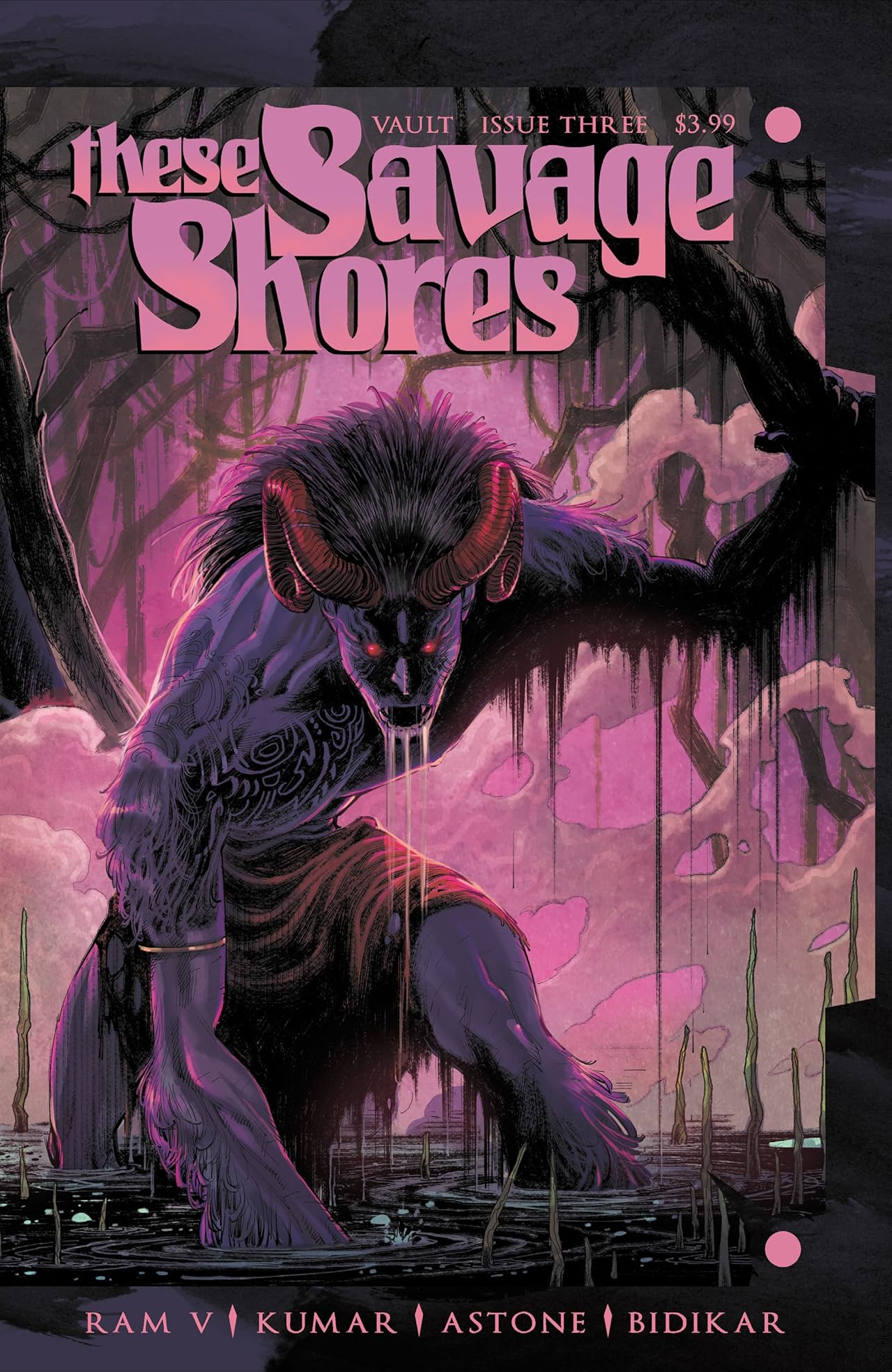

These Savage Shores

by Ram V, Sumit Kumar, Vittorio Astone,

and Aditya Bidikar

Vault Comics

Part classic horror story, part post-colonial satiric reflection, These Savage Shores is a gripping account of the East India Company's attempts to take full control of the Silk Road in the late 1800s. Ram V chooses to frame this story as a horror narrative, and he mixes history with mythology to create something altogether new. I'm already a sucker for the history of nations, and I find the end of the feudal era to the rise of the colonial era to be of particular intrigue. Regardless of that predilection, These Savage Shores is a compelling read in its own right. Ram V is a rising star, and he pairs with newcomer Sumit Kumar for what turns out to be an absolutely beautiful book. Kumar has a knack for texture and shade. His pages are intricate and layered. Of course, he's aided by the fantastic Vittorio Astone and Aditya Bidikar, arguably in the conversation for best colorist and best letterer of the year, respectively. Wordie's colors allow Kumar's lines and textures to feel even deeper, and Bidikar is adept at complementing Ram's script. Ram V's narrative here is straightforward, but it is engaging in its simplicity. There aren't a ton of twists and turns, and the reveals are kept subtle and pointed. But that's part of the beauty of it - this is a story of war, and the losses that come along with it. Ram thoroughly concludes this part of the story, but leaves plenty of opening to return to this world, and I pray he does.

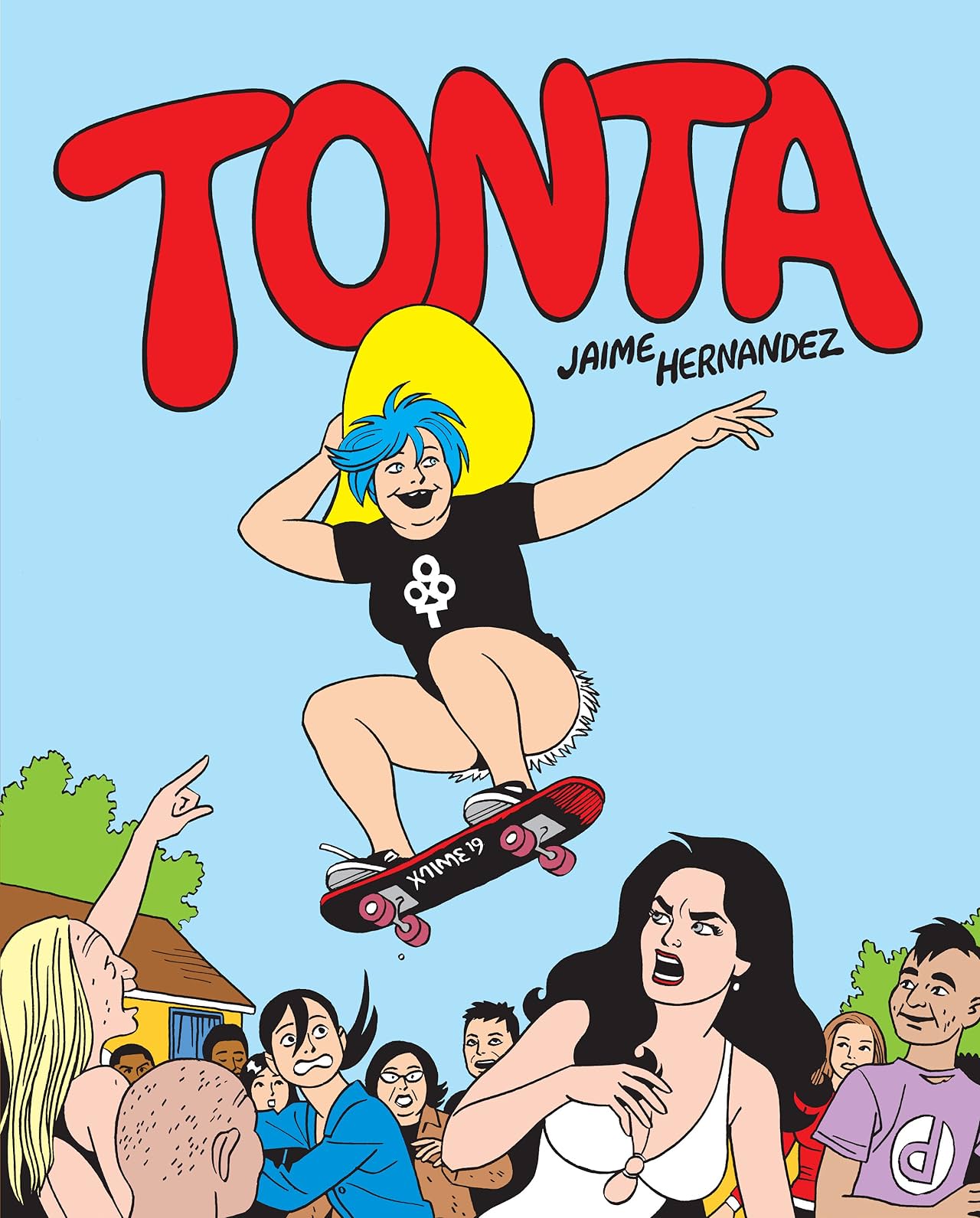

Tonta by

Jamie Hernandez

Fantagraphics

Love and Rockets has been going strong since its most recent revival, but Tonta isn't a collection of previously published stories. These stories about the titular character have been percolating on Jaime's writing desk for quite some time, and this story reads much more like a complete graphic novel than the typical L&R collection. Tonta is a captivating character because she's alternates between being relatable and frustrating. She's sympathetic one moment and annoying the next, too cool for petty drama and then wrapped up in her own. At first I rolled my eyes, and then I remembered that's exactly what the adolescent mind is - a rollercoaster of emotion and interests that wants popularity one minute and punk rock the next. Because Tonta is a new character, we don't have the thirty year relationship with her that we do with other L&R crew. As a result, she is a new, and the story feels familiar but fresh. It's confessional and introspective in the way we'd expect, but it's also original.

Wasted Space

by Michael Moreci, Hayden Sherman,

Jason Wordie, and Jim Campbell

Vault Comics

To think we might have never had this whole second arc of Wasted Space, the series that has come to define a certain brand of post-modern space opera for me. Moreci knows his sci-fi, and he has crafted a wonderfully complex story of politics and religion and power and sex robots that really like to get weird and redemptive heroes and, well, I could keep going for a while here. Hayden Sherman continues to defy the rules of modern mainstream books and pushes an avant garde, almost cubist approach. I wrote before that Sherman reminds me of Jimmy Page eschewing technical precision to bang on a guitar to elicit all types of new sounds. This year’s arc features the team coming to terms with the new status quo, and finding themselves as heroes of sorts, on a mission to save the universe they’ve just upended from nuclear annihilation. Billy continues to develop as a leader like the other great reluctant schmucks who a thrust into something far too big for them to either handle or ignore – James Holden, Peter Quill, or Mal Reynolds. Wasted Space continues to be the first book I read on the weeks it arrives in stores. It’s the funniest, most engaging book every time.

The Wicked and the Divine

by Kieron Gillen, Jamie McElvie,

Matt Wilson, and Clayton Cowles

Image Comics

*Library Book*

The third of three long running independent series on my list concluding their runs this year, The Wicked and the Divine is a one of a kind series. As a meditation on the fleeting nature of life, and more specifically youth, it's the kind of book with a beautiful feel covering up an ultimately tragic story. From the onset of the series, Gillen has built to the final arc by teasing the idea of controlling the power of the Pantheon, playing with the role of Ananke, and hinting at the idea that this incarnation of the Pantheon is destined for different things. A final arc of a series can be difficult to execute, but Gillen and McElvie turn up the pacing and the tension to drive towards the finish, delivering a fantastic final issue in #44 and an even better epilogue with #45. There's a rare contentment at the end of a series that wraps up so well. It's bittersweet, but it reminds one of the journey itself, which, coincidentally enough, is what Wicked and Divine was always mining - temporal impermanence and the stubborn battle against it.

Three quick notes about list construction: First, I stress the term favorite, as all of the Panel Patter crew does, not to deflect, but to emphasize that these are the comics that most resonated with me over the course of the year. They are by no means the best. I suppose they are the best for me, but that's the point. I'm hopeful that a few readers see books they haven't read this year and decide to give them a try. More than anything else, this is a thank you to the creators of these wonderful comics. Second, I have a specific criteria for publication dates and formatting. Serialized books published prior to 2019 now collected into trade are not necessarily eligible for my list. Obviously, if I am including a serialized book, I'm referring to what hit the shelves monthly in 2019. But a series that saw the majority (if not all) of it's monthly issues published in 2018 before a collection in 2019 doesn't show up on my list. Thus, Mister Miracle arrives on many critics "best graphic novels of 2019," but it's a 2017 or 2018 book for me. I've gone with a fairly arbitrary 30-40% published rule for limited series and a three issues published rule for ongoing series. Other books that I loved that fall victim to that system are Fearscape (included on my 2018 list) and Friendo (criminally neglected via file merge error from my 2018 list, but it's great and you should buy it). I make exceptions for books that collect serialized stories published over a long stretch of time, but more on that below. Third, I'm not specifically ranking any of these books outside of my favorite overall comic and my favorite superhero book. After each of those, the list proceeds alphabetically by title. I also put my two favorites first rather that at the end of this post.