Art by Mahmud Asrar

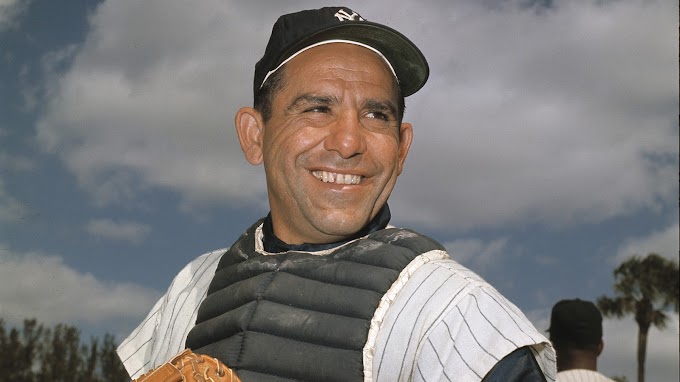

The first story in Jason Aaron and Mahmud Asrar’s Conan the Barbarian climaxes with a near-killing blow as two daggers are plunged into King Conan’s back (that’s right, KING Conan.) This initial chapter spans a period of time from when Conan was a wandering adventurer to his days as the king, foreshadowing the time-hopping structure of this Conan story. The Life and Death of Conan is one large story about Conan’s last days, as a threat that he encountered years ago has waited in the shadows, alleyways, and battlefields for the ultimate moment to strike and take Conan’s life. But within that story of this ageless evil waiting to be unleashed with Conan’s death, Aaron, Asrar and occasional Geraldo Zaffino show what Conan’s life was like, telling tales of the warrior at different stages in his constant and unending battles. You could almost imagine that with those two daggers are stuck in his back, Conan’s life flashes before his eyes, remembering the battles, the victories and the women who got him to this deadly point.

But here’s the thing about Conan: if you’ve read one Conan story, you’ve pretty much read them all. Sure, the locations can change; Cimmeria, Hyperborea, Aquilonia, Argos, Stygia and other more ominous Tolkienesque-sounding names. The adventure can change. The enemies of Conan are numberless and the women are plentiful. The richness to the world that Robert E. Howard created has only grown in small steps over the years as the different characters, particularly the female characters, are allowed to be at least a bit more than arm candy for Conan but that richness is completely lost in this incarnation of Conan The Barbarian. The Conan that Aaron is writing isn’t that different than the character that Kurt Busiek did for Dark Horse or the character that Roy Thomas spent a better part of the 1970s and 1980s writing during Marvel’s first tenure with the character.

Ultimately, Conan just isn’t much of a character. He functionally acts as a plot device, creating an environment for these sword & sorcery stories to exist. He’s the gravitational center that holds these stories together. And that’s good because he’s a fun vehicle for these kinds of stories. He’s a simple character who gives us and the creators a solid footing in this world. This “hero” gives Aaron a hook to craft these stories around and provides a foundation for Asrar to apply his skills to. But there’s no narrative here; there’s no development in what Conan thinks or feels. There’s no expansion of this world beyond what the likes of Windsor-Smith, Buscema, or (more recently) Nord or Cloonan have done and accomplished. The sensation of what a Conan comic is was written in stone decades ago and nothing that Aaron or Asrar accomplish make any great or meaningful changes to that stone.

Art by Mahmud Asrar

What Asrar does bring to this world is a modern polish that’s contrasted by Esad Ribic’s Frazetta-inspired covers or the rough and aged stories drawn by Gerardo Zaffino. Zaffino created depth in his drawings; Asrar created barbarian style. As witches are getting their head lopped off, blood vividly spraying everywhere (which we’ve got Matthew Wilson to thank for) and monstrous creatures attack Conan, Asrar makes it look just so damn handsome and manly. He takes the physicality that John Buscema gave the character and makes it something worth the female and even the male gaze. His Conan, bare-breasted and dripping in blood and sweat, is also a sex object, even when there’s no sign of a female around him. We’ve moved far past the Conan who was a warrior to a Conan who is a barbarian sex object.

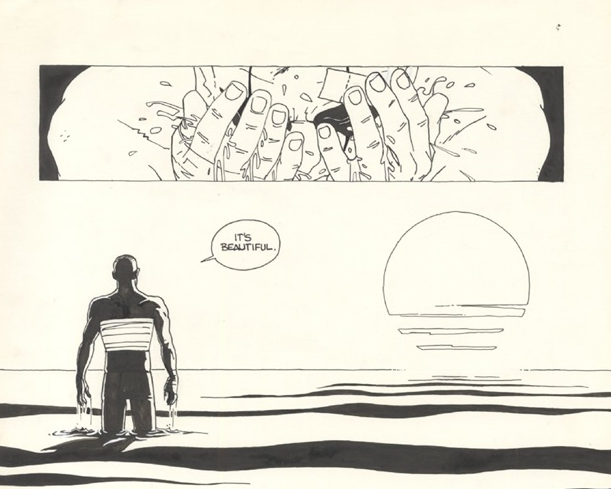

The most character-revealing chapter of this cycle of Conan stories comes in the eleventh chapter (found in Book Two,) after Conan dies (well, it’s a comic book death so you know what that means) and meets his god Crom. Most people would be humbled and worshipful when meeting their idea of the supreme being but this is Conan we’re talking about here. As Crom is about to turn his back on the world that Conan recently departed, Conan fights for something other than himself. Throughout Aaron’s stories, it’s tough to find the motivation for Conan’s constant battles other than Conan himself is just a fighter. It’s what he does. This is shown in the first Zaffino drawn issue (a fantastic story of a restless king) and it re-emphasized in the eleventh part of these books. Conan is a fighter and he will not accept that his god isn’t.

Where that restless king meets his deity, Aaron, Zaffino, and Asrar define Conan as a man who needs to fight. It’s his nature but it’s also his calling. And they show that over and over in these books, without the subtext of those two superior stories to define what it is that Conan is fighting for or about. For Conan, it’s not even really a moral drive; there’s no sense of right and wrong. If Conan fights an evil force or a corrupt politician, there’s an air of non-judgment in these stories because he isn’t fighting in terms of right or wrong. He’s fighting in terms of “Conan” and “not Conan.” You’re either helping him or your not. It’s as simple as that.

So motivation is largely not a real factor when it comes to these comics and stakes barely matter either. The comics, like Conan, exist in the moment and don’t stretch out much beyond that. Aaron and his artists create some fun issues, have the occasional poignant moment (maybe about three or four in total in these two books) and occasionally nod wistfully at the history and backdrop of Howard’s original stories. It’s the appearance of having something to say about Conan and these types of stories without ever having to commit to ever really doing anything with these stories. That’s the trap of this kind of mainstream characters; they’re trapped in the amber of their original stories, forever preserved in those moments and kinds of stories.

But Conan and his stories were never those kinds of character-driven and motivated stories. They’re about swords, women, and fighting, which are the things that Aaron and Asrar seem to be grooving on here. It’s easy to just get lost in the pulpy nature of these stories. Asrar and colorist Matthew Wilson bring this visceral violence to life in a way that’s both shocking and also completely appropriate and exciting for these stories. The brutality of these kinds of fantasy stories (see almost any episode of Game of Thrones; it’s basically the same thing violence wise) turns into a colorful dance of movement and blood. These are fun stories to look at thanks to Asrar and Wilson. They’re doing the fun work while Aaron is largely sticking to a formula that was established a long time ago. Are we not entertained?

After having told some incredibly character-driven stories in Thor and (to a lesser state of completion) Southern Bastards (reviewed here and here), Aaron seems to be working in a story-for-stories’ sake right now. That’s evident in his Avengers works as much as it is here in Conan as the surface-level plots of these books seem to be as far into the characters and their thoughts as he’s able to dive right now. In this recent work, his writing is driven more by story beats than by character development and part of that maybe because he’s dealing with these long and deeply established characters who have to serve their corporate masters a tad bit more than his more personal work does. Conan is a vehicle to be driven much more than a character to be explored and plumbed.

This lack of heart makes these not much more than pretty drawings and flowery words. In between those drawings and speeches, there are hints of a great love and of a legacy for Conan but that’s all they are— hints of a deeper and grander story. This isn’t so much a judgment of Aaron and Asrar’s work as it is an indictment of Robert E. Howard’s Conan himself. Here’s a character that practically defies any real depth of being. Of course, if there was any depth here, the character probably wouldn’t be Conan at that point but more of a Conan-like character. Instead of a fleshed-out, human-like character, Conan is a plot device that lives each moment panel by panel (it is a comic after all) as if there’s no moment before the current panel or after it.

And frankly, that is why the two Zaffino stories work so much better than almost anything else in these books. There’s a fading past in those stories as well as a bloody current and an uncertain future. There are actions that happened and consequences that were paid or are still owed. Zaffino captures that painful past in his drawings of Conan that Asrar can never really tap into. If Asrar’s Conan lives in the present moment, Zaffino’s lives in the memory of the past. Aaron gives Zaffino these stories that demand Conan to be more introspective and self-aware. Conan has a responsibility here that’s absent in the Asrar drawn stories. There’s an ethos that Zaffino can pull out of Aaron’s story, a richness to them where Asrar’s version of this world is incapable of tapping into any kind of true pain, either physical or spiritual.

So, what does this character who’s been appearing in comics since the 1970s mean to us today? Maybe that’s an unfair burden to place on these stories, that they have to have some kind of relevance in 2020. But if they don’t, then what’s the point? Is this just Jason Aaron and Mahmud Asrar simply playing with Marvel’s newly found toys? It feels like Conan comics exist now because why shouldn’t they? Marvel seems to be doing everything it can to make the character relevant in terms of the Marvel Universe such as being part of an Avengers team or crossing over with Moon Knight. That’s one approach to the character, trying to make him a superhero but Aaron, Asrar and Zaffino take a much more traditional approach to the character that manages to show what makes this character endearing but also what makes him a character out of time and context.

Conan The Barbarian: The Life and Death of Conan Books One and Book 2

Written by Jason Aaron

Drawn by Mahmud Asrar and Geraldo Zaffino

Colored by Matthew Wilson

Lettered by Travis Lanham

Published by Marvel Comics